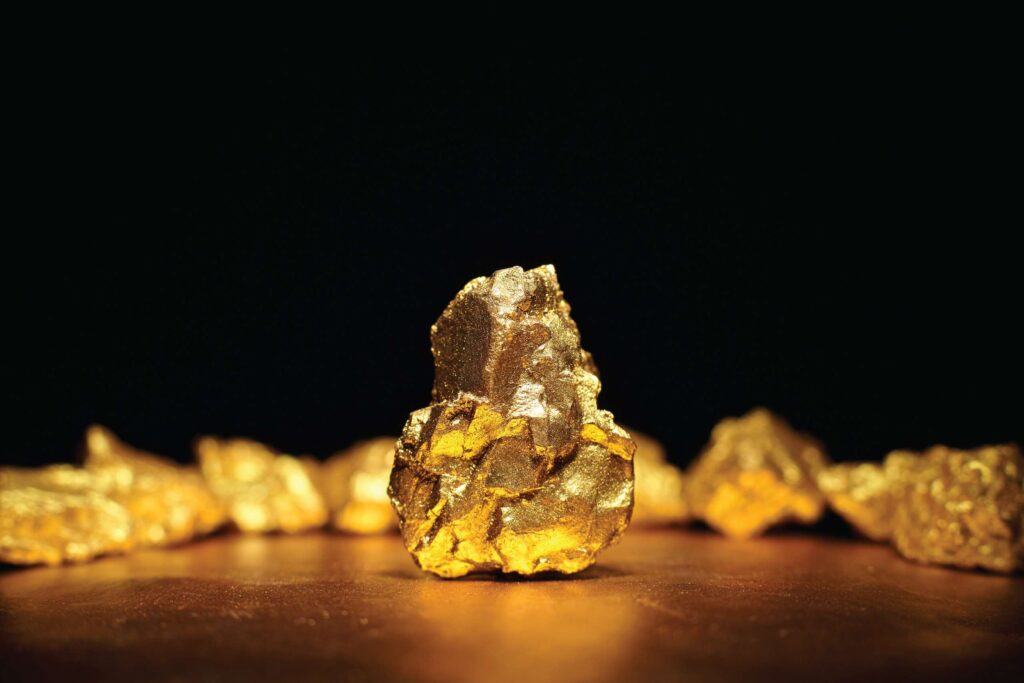

Precious Metals

The Other Side of Trump’s Tariffs: Ghana’s Toxic Gold Rush

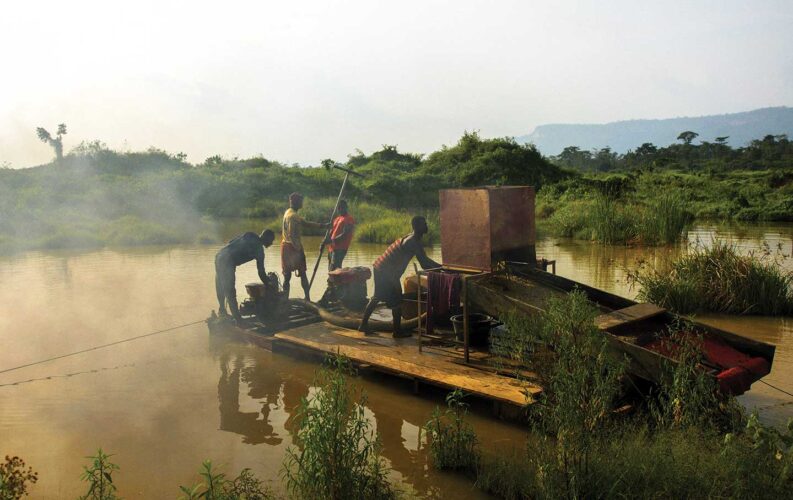

The landscape along the road approaching Konongo, in Ghana’s central Ashanti Region, had the feel of a sprawling construction site. On either side of the potholed thoroughfare, mounds of cinnamon-colored dirt lurked just beyond the sparse greenery. Hulking excavators dotted the area, both at the roadside and off in the distance, straddling fields punctuated by turbid, muddy ponds.

It hadn’t always looked this way. “That’s the river we used to swim in as kids,” said Bobby Bright, gesturing out the window of a Mitsubishi Mirage. “We used the water for drinking and for irrigating our cocoa farms.”

The river in question was the color of coffee with heavy cream. It didn’t appear to flow at all. Bright, a 50-year-old IT specialist turned environmental activist, grew up in Konongo on a farm that was owned by his grandfather. In 2017, having completed his university degree, Bright returned to Konongo with a plan to take up the cocoa and oil palm farming of his ancestors. But the hamlet’s trees had all been cut down. Bright’s uncle, like many in the region, had sold the family land to gold miners and promptly disappeared with the cash. Today, the cocoa and oil palm trees—like the fields of cassava, corn, and plantain that were also cultivated throughout Ashanti—are gone. They’ve been replaced by a jumble of cement-block homes interspersed with those ugly mounds of soil and murky ponds—the visible signs of a ferocious gold rush that has, not for the first time, upended life across Ghana.

For centuries, gold has been both a boon and a curse for this region. It was the area’s gold reserves that enabled the Ashanti Kingdom to emerge as one of West Africa’s most powerful in the late 1600s—just as it was gold that led to its undoing when the British, lured by the precious metal, descended on the land and, in the 19th century, ultimately colonized it. Ghanaians would not win independence until 1957.

Observers of this latest gold rush trace its origins to the global instability of the past few years, beginning with Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. That jolt, in 2022, sent investors worldwide flocking to gold—known as a “safe-haven asset” for its enduring value—causing its price to soar. A year and a half later, the uncertainty ushered in by the war in Gaza drove the price of gold even higher. And then, earlier this year, came Donald Trump: His tariff threats turbocharged the phenomenon, with the price of gold hitting an all-time high in April.

As these events unfolded, they rippled across the world to Ghana, more than doubling the value of the country’s gold exports—and stoking an epidemic of illegal mining. This illegal version—a corruption of an old artisanal form of mining known as galamsey (a contraction of “gather them and sell”)—has exploded, as foreign nationals, mostly from China, have exploited the trade, and young locals, desperate for work, have jumped at the opportunity. Today, galamsey accounts for more than a third of Ghana’s annual gold output.

The result of this bonanza has been a fast-moving disaster, one that’s fueled multiple converging crises. The environmental impact has been particularly profound. As galamsey has spread, forests have been felled, earth torn up, and the once pristine countryside contaminated by heavy metals. Lead, cyanide, cadmium, arsenic, and mercury—especially mercury—have poisoned both land and water. “The devastation we are seeing in our forests and water bodies is beyond alarming,” said Muhammad Malik, of the Accra-based Climate Change Africa Initiative. “Illegal mining is stripping the land bare, polluting rivers, and killing ecosystems. If we don’t stop this, Ghana will face an environmental collapse [from which] we may never recover.”

But the fallout goes beyond decimated forests and toxic waterways. Among galamsey’s other obvious casualties is Ghana’s all-important cocoa industry. The world’s second-largest cocoa producer (after the Ivory Coast), Ghana is home to more than 1 million cocoa farmers, most of whom tend small plots of just a few hectares that have been in their families for generations. The sector remains central to the Ghanaian economy, responsible for more than 20 percent of export revenue. But as the country’s gold exports have ballooned, cocoa production has tanked: Whereas gold receipts soared from $5 billion in 2021 to $11.6 billion last year, cocoa earnings shrank by more than a third—from $2.8 billion to $1.7 billion—over the same period. Many cocoa farmers, already struggling with climate-change-driven weather instability and a rampaging tree virus, are selling their land for the ready cash offered by miners. Others, like Bright, are being forced off their land. In May, Ransford Abbey, the CEO of Ghana’s government-controlled Cocoa Board, reported that 50,000 hectares of cocoa farms were at risk from illegal gold mining, among other threats.

“We’re facing the most serious crisis in the sector’s history,” Abbey said.