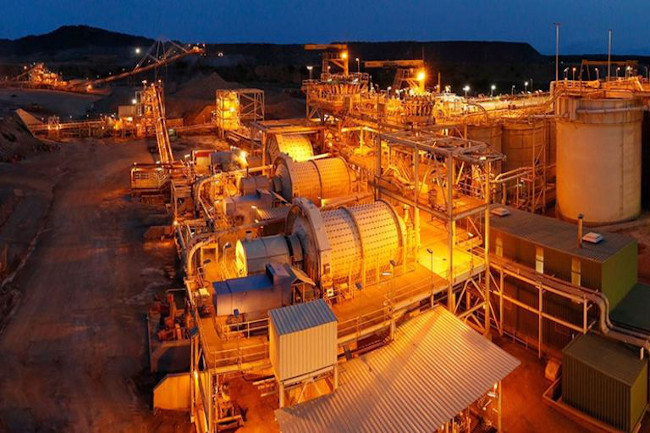

Mining Other

South Africa’s thin-incentive critical minerals strategy noted in G20Lens analysis

Investment incentives are thin: there are no tax holidays, royalty relief or other targeted financial measures to attract exploration and critical‑mineral development.

Minerals are ranked by criticality, but there is no differentiated regime to operationalise that ranking.

Beneficiation goals are aspirational given constraints in power, logistics and port performance.

Regulatory uncertainty persists, with the May 2025 Mineral Resources Development Bill including requirements for mandatory beneficiation by producers but leaving key investment issues unresolved. An actionable implementation plan with accountability mechanisms has not been published.

ENS natural resources and environment department head Ntsiki Adonisi, ENS executive Ghana Rachel Dagadu, ENS natural resources and environment senior associate Zinzi Lawrence, ENS associate Namibia Amarachukwu Odo, and Mulenga Mundashi associate Zambia Chimwemwe Tembo-Shula state this in ENSafrica’s latest ENSight, published under the banner of G20Lens.

Africa possesses a significant share of the minerals essential to the global shift towards clean energy, from platinum group metals (PGMs), cobalt and copper to lithium, but the core challenge is moving beyond extraction to develop integrated value chains, create jobs and share benefits equitably and sustainably.

Africa holds more than 30% of global critical mineral reserves. These resources can drive economic transformation through well-managed value addition, industrialisation, large‑scale job creation and regional market creation, underpinned by environmental management.

If handled poorly, Africa risks repeating the past: continued export of low‑value raw materials, importing high‑value finished goods, exploitative outcomes and environmental degradation that exacerbates climate impacts, losing the midstream to other regions and missing the capital now flowing to bankable, policy-aligned projects.

Global industries are retooling for a low carbon economy, and Africa’s geology is central to achieving that.

Commercial‑scale deposits of lithium, manganese, nickel, copper and rare earth elements (REEs) position Africa as a key supplier, with the Democratic Republic of Congo dominating global cobalt supply, South Africa having significant reserves of PGMs and manganese, Guinea holding a major share of bauxite reserves, Ghana also prominent in manganese, and Namibia hosting lithium.

Internationally, policy frameworks are wanting supply chains for these minerals, an opportunity Africa can leverage to accelerate industrialisation.

Africa’s mineral endowments are aligned to electrification, industrialisation, regional offtake and supplier development driven by Africa's Green Minerals Strategy, the African Mining Vision and the African Continental Free Trade Area, ENSafrica states in its release to Mining Weekly.

Jurisdiction definitions

The analysis of South Africa’s Critical Minerals and Metals Strategy, published in May 2025, is that it adopts a context‑specific definition: critical minerals are those essential for overall economic development, job creation, industrial advancement and contribution to national security.

South Africa’s critical minerals list, the release points out, is informed by export significance, industrial importance, economic contribution, development alignment and global demand.

The strategy identifies 21 minerals, grouped by criticality. High criticality minerals include platinum, manganese, iron-ore, coal and chrome; minerals with moderate‑to‑high criticality include gold, vanadium and REEs; and minerals with moderate criticality include copper, cobalt, lithium, nickel and uranium.

Ghana has no statutory definition or fixed list of “critical minerals”. Policy references appear in the Minerals and Mining Policy and the 2023 Green Minerals Policy (awaiting parliamentary approval), which highlights battery‑related “green minerals” such as lithium, bauxite, manganese, nickel, copper, cobalt and graphite.

In practice, Ghana’s view of criticality extends beyond green minerals to resources essential to economic security, electrification, domestic value addition and resilient supply chains.

Given Ghana’s position as Africa’s leading gold producer, gold accounts for roughly 90% of mineral exports and is a major GDP contributor. Gold is integral to Ghana’s conception of critical minerals, however other critical minerals such as lithium, bauxite and manganese are receiving increased attention.

Zambia’s national critical minerals strategy, passed in 2024 for five years, defines critical minerals as naturally occurring minerals crucial to contemporary technologies and national growth, especially for green energy applications such as solar PV, wind turbines and electric vehicle batteries.

Zambia’s list includes cobalt, copper, graphite, lithium, manganese, tin, nickel, REEs, sugilite and uranium, reflecting their importance to domestic development and global technological advancement.

The first of the four strategic objectives of Zambia’s strategy involves advancing geological mapping and resource management through training and use of advanced technologies.

The second centres on enhancing government and private sector partnerships.

The third promotes value addition by encouraging local processing and offering tax incentives, and the fourth advocates fostering research and development (R&D).

In summary, the four objectives seek to ensure that Zambia’s geological knowledge increases steadily by increased support toward geological mapping, to ensure efficient mining and exploration.

The government further seeks to encourage government and private sector partnerships, by among other things, the formulation of policies that bolster investor confidence in the mining sector.

In addition, the government seeks to incorporate a special purpose vehicle that will hold a stake in new critical mining ventures.

Local value addition is seen as an industrialisation enabler and employment creator and the Zambia government seeks to invest in R&D to foster development of research hubs for the benefit of the mining sector.

Zambia’s 2026 budget allocates funds for mineral processing hubs, marketing centres, geological mapping (with about 34% of the country mapped as of 2025) and R&D, including support for university‑based mining research hubs. The budget also earmarks funding for dedicated research hubs aligned to the national strategy, to advance mining technologies and strengthen environmental protection.

Namibia has no formal definition or fixed list of critical minerals, but the 2021 Minerals Beneficiation Strategy identifies ‘strategic’ minerals that functionally serve as critical. Assessment factors include relevance to the green transition and domestic abundance.

On this basis, Namibia views uranium, copper, lithium, manganese, graphite and selected REEs as critical, given their roles in national planning, job creation and the clean energy value chain.

In May 2025, Namibia banned exports of unprocessed lithium, cobalt, manganese, graphite and REEs to incentivise domestic processing capacity. International partnerships on rare earths aim to anchor investment, job creation, skills transfer and position Namibia as a reliable global supplier.

Enable sustainable value to be released

Opportunities lie in Africa’s resource base and the ability to unlock prospectivity through better geoscience, disciplined and high‑quality open data, clear work‑programme obligations with renewal caps and State relinquishments, the report states.

Many jurisdictions, including Ghana, have licensing frameworks that support investor certainty, while community benefit mechanisms are maturing.

Governments are increasingly negotiating project‑specific terms, such as higher royalties, larger free‑carried interests and State and local equity to share in the upside and anchor local beneficiation.

Key bottlenecks include limited and outdated geoscientific coverage in several countries (for example, Nigeria and Côte d’Ivoire and, to an extent, Ghana), fragmented and onerous multi‑agency permitting that causes delays and adds cost, and policy volatility (including changes driven by political instability) that affects local‑content rules and tenure certainty.

For mineral export bans to be effective, they must be paired with enabling conditions: bankable projects, reliable and affordable power, efficient logistics and legal certainty. Without these, bans tend to suppress production, increase informality and trigger force majeures and possible breaches by mining companies in respect of their long-term offtake agreements.

The path forward

Africa’s critical minerals can be a catalyst for diversified growth, resilient supply chains, inclusive development and creation of regional markets.

Converting geological advantage into industrial capability requires coherent strategies that link mining, energy and industrial policy; investment in enabling infrastructure and skills; modernised licensing and data systems; and provision of regulatory certainty with clear implementation pathways.

With these elements in place, Africa can move decisively beyond extraction towards building competitive value chains that create jobs, deepening local participation and delivering sustainable prosperity, the five authors state.