Mining Other

Zambia’s Sacrifice Zone a legacy of toxic mining

Kabwe, Zambia, is one of the most polluted towns on the planet – 200,000 of its residents have lead poisoning caused by nearly a century of mining.

It’s what experts call a “sacrifice zone”.

It’s a place that’s been permanently contaminated by nearly a century of lead mining. A 30m-high pile of mine waste still looms over the town, and every gust of wind spreads its toxic dust across Kabwe.

Despite the dangers, hundreds of people risk their lives to mine the area for leftover minerals. The waste has even earned the nickname “Black Mountain”.

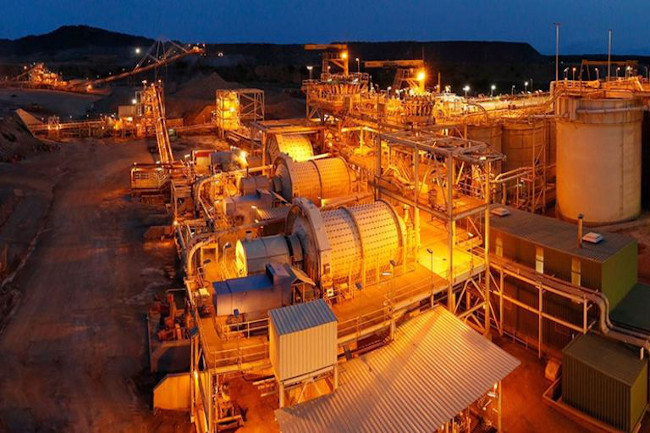

Today, backed by US tech billionaires, a new wave of copper mining is sweeping across Zambia.

When Oliver Nyirenda was growing up in Kabwe he loved playing soccer. But after every game his feet, clothes, even his eyelids, would be covered in dust. It scared Oliver’s mother so much that she banned him from playing soccer. Because she knew that inside the dust is a silent killer that claims nearly a million lives around the world each year.

Oliver was diagnosed with lead poisoning at two years old. His lead levels were 117 micrograms per decilitre – more than 20 times higher than the World Health Organization’s threshold. His mother remembers how he would get confused and forget simple tasks. All the clinic could offer was a nutrition-based treatment plan, which at the time formed part of an initiative to combat lead poisoning in children.

“The government used to provide milk, soya and eggs for us who were poisoned by lead,” he says.

From solar panels and wind turbines, to batteries that power electric vehicles, copper is an essential mineral for building clean-energy technologies to slow down climate change. However, an increase in demand for it means more mining.

Zambia’s government says it plans to triple the country’s copper production over the next six years.

Today, 18-year-old Oliver faces a profound choice to improve the way mining is done: does he remain an activist and fight for the rights of his community from the outside, or try to work his way into the very same industry that poisoned him as a child?

Oliver thinks mining could be done better. He says it’s not mining itself that is bad, but how it’s done. He has faith that a better mining future is possible.

So, as countries across Africa scrutinise their contracts with foreign mining companies, Oliver wants the industry to do better, and residents in mining communities want to decide how mines are run and how profits are used, as well as hold polluters accountable.

“If things do not change this time around, then I don’t think the Zambian people will allow it. If they don’t care, then they have no right to take the minerals,” he says.

Radio Workshop’s editorial director, Lesedi Mogoatlhe, says: “Oliver’s story speaks to the resilience of young people who have inherited the residue of bad mining practices.

“Youth in mining towns all over the African continent need to be at the centre of conversations about a sustainable future in mining as the world looks to mining transition minerals. Young people are asking for clear, meaningful involvement to ensure that the environmental and human rights abuses from mining are not repeated.” DM