Precious Metals

Their diamond-rich land in South Africa was taken - Now they want it back

A disturbing contrast marks South Africa's remote west coast. The 800km journey north from Cape Town begins with views of outstanding natural beauty, which dissolve into a pockmarked, lunar-like landscape as the road approaches the northern border. The scars left by the lucrative diamond-mining industry are not merely physical. The impoverished local Nama community, living amid this environmental degradation in the far north-west region also known as Namaqualand, wonders what happened to the riches their land yielded. While hundreds of millions earned from the diamonds went toward building the country, little appears to have stayed within the area.

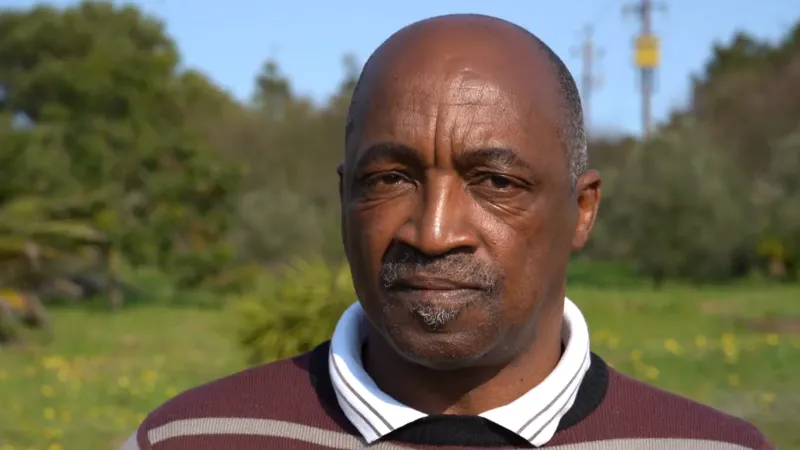

The Nama, who straddle South Africa and Namibia, are descended from the indigenous Khoi and San peoples. Despite winning a landmark legal battle over land and mining rights in Richtersveld more than two decades ago, many in the community argue they have yet to see any benefit. Andries Josephs, who once worked in the now-declining diamond industry, stands amid the wrecked empty shell of a former mineworks in Alexander Bay. He shakes his head, noting the absence of work, the stagnation of the people, collapsed buildings, and sky-high unemployment. The diamond industry’s decline has left a trail of economic and social problems.

Approximately a kilometre from the derelict mine lies a residential area with a few houses, a broken-down church, and a hospital with damaged windows. The local authority’s development plan describes dilapidated water and electricity infrastructure and poor roads, which hinder access to essential services like healthcare. A century ago, the discovery of diamonds south of the Orange River triggered a rush that changed the land forever. Yet the Nama had known of the gems for generations. Martinus Fredericks, appointed by Nama elders in 2012 as their leader in South Africa, recalls that children in his family were once taught to count with diamonds.

The Nama were historically herders and traders until European settlers interrupted their way of life. Their land was annexed in the mid-19th century by the Cape Colony, and after diamonds were found in the 1920s, they were cleared from areas around the Orange River. This situation persisted through apartheid and after the advent of democracy in 1994. The new ANC-led government maintained that the diamond wealth should serve the greater national good. Following a five-year legal battle, the Constitutional Court ruled in 2003 that the Nama had an inalienable right to their ancestral land and its minerals. However, in 2007, a deal was struck with the Richtersveld Communal Property Association (CPA)—which purportedly represented the Nama—granting the state-owned Alexkor mining company 51% of mineral rights, with 49% going to the community.

Martinus Fredericks argues that the CPA did not represent the Nama and that the agreement was made without the wider community’s consent. He alleges that, twenty years on, the community has yet to profit from the deal or from decades of diamond wealth. Alexkor disputes this, stating it has paid 190 million rand in reparation and a 50-million-rand development grant to the Richtersveld Investment Holding Company. Alexkor’s board chairperson, Dineo Peta, acknowledged the community has not received the full economic benefit, blaming past “maladministration and malfeasance” within the company. Previous management was implicated in a state capture investigation, though no convictions have ensued.

At a recent parliamentary hearing, lawmakers heard that the CPA was “dysfunctional” and that over 300 million rand paid to it had not reached the community. The CPA did not attend the hearing and has not responded to BBC inquiries. Beyond financial concerns, Fredericks highlights environmental damage, alleging that large mining companies extract resources without proper rehabilitation, leaving the community to deal with the aftermath. Abandoned mines, like one in Hondeklipbaai formerly owned by Trans Hex, show little sign of restoration. Trans Hex stated it met its legal obligations while it held the mining right but is no longer responsible since selling the site. De Beers, which sold its west coast interests, committed 50 million rand to support rehabilitation as part of its sale agreement.

There are now concerns that environmental damage may spread south as mining activity edges down the coast. Requests for comment from the departments of forestry, fisheries, and the environment went unanswered by the previous and newly appointed ministers. Fredericks is clear that the government should return what belongs to the Nama. He has begun legal action against the CPA, arguing it was not properly constituted. For the Nama, he asserts, there is an intrinsic link between the people and the land: a Nama people cannot be without control of Nama land.