Base Metals

Cobalt rally risks pushing away battery makers, top miner says

“I think it’s at the upper end of what people will tolerate without being forced to switch,” Kenny Ives, chief commercial officer at CMOC Group, told Bloomberg News in London on Tuesday.

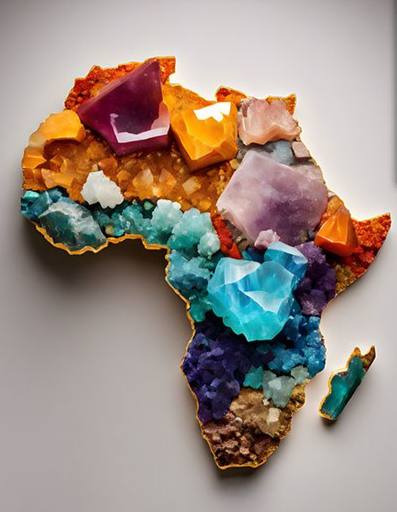

Congo, which accounts for about three-quarters of output of the material used in electric-vehicle batteries, aerospace and the defense industry, has introduced controls to rein in oversupply. An eight-month ban on shipments will be replaced by strict quotas later this week.

The suspension was announced in February after benchmark prices had dropped below $10 a pound, a level not breached for 21 years, bar a brief dip in late 2015, according to Fastmarkets data. But cobalt has doubled since then, while the price of cobalt hydroxide – the main product exported from Congo – has more than tripled.

Despite the sharp rally, prices are still less than half what they were during peaks in 2018 and 2022.

Congo has said that miners can export just over 18,000 tons of the metal during the remainder of this year and a maximum of 96,600 tons in each of 2026 and 2027. The volumes permitted to leave Congo in each of the next two years are less than half the country’s production last year.

CMOC is particularly impacted by the new restrictions. Next year, the Chinese firm will only be allowed to ship a volume equivalent to about 27% of the 114,000 tons of cobalt it produced in 2024 from its two mines in Congo.

“If you starve the downstream of cobalt units, clearly there are different chemistry options and the Chinese and others will switch,” Ives said – adding he suspects Congo will reconsider the quota “on a semi-regular or a regular basis.” Most EV manufacturers in top EV producer China have already turned to lithium iron phosphate – or LFP – cells that don’t use cobalt.

The quotas won’t stop CMOC mining even more cobalt, however, because the metal is extracted in Congo alongside copper, which is trading just below record prices and widely anticipated to perform even better in the coming years.

CMOC’s copper output from its pair of Congolese mines will hit 700,000 tons in 2025, nearly 8% more than last year, and “grow significantly over the next three, four or five years,” according to Ives, who’s also the chief executive officer of CMOC’s trading unit, IXM. “That produces a lot of cobalt.”

While the cobalt market was “saturated” when Congo imposed the ban, it wasn’t simply because of the rapid ramp-up at CMOC’s mines in the country, according to Ives. Demand growth for the metal has also been “very underwhelming for years,” he said.