Base Metals

Cobalt Crossroads: Why Indonesia Still Trails Behind the DRC in the Tech Supply Race?

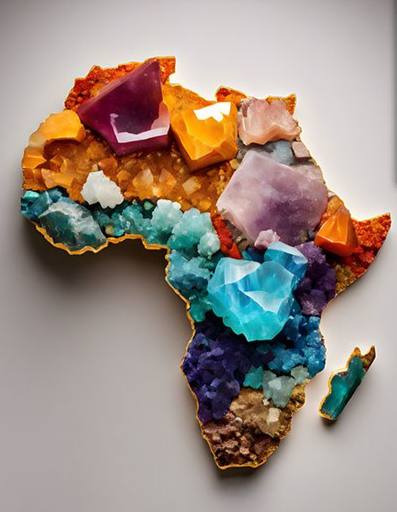

The Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) is widely recognized as the world’s largest producer of cobalt, accounting for around 70% of total global output. Numerous foreign mining companies operate in the DRC, employing local miners and simultaneously contributing to the country’s foreign exchange earnings. However, the country’s mining practices face significant challenges in meeting Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) standards, challenges that risk disrupting the supply chains of global technology firms. Despite this, many major tech companies still prefer cobalt sourced from the DRC over exploring alternatives like Indonesia, another resource-rich nation. Indonesia ranks as the world’s second-largest cobalt producer, increasing its output from 19,000 metric tons in 2023 to 28,000 metric tons in 2024. Yet, this increase has not been enough to entice big tech firms to shift their supply strategies. Why is that?

In the DRC, several foreign mining firms are in operation, one of the most prominent being Glencore’s Kamoto Copper Company, which has operated since the 1970s. Glencore supplies cobalt directly to global tech giants like Microsoft, Google, Tesla, and Apple, making it the largest cobalt supplier among foreign mining companies in the region. These firms prefer direct procurement from Glencore without intermediaries or third-party processors, allowing them to conduct due diligence directly on mining practices, with an emphasis on transparency and auditability. In contrast, third-party suppliers such as China Molybdenum, seen as indirect partners, limit traceability and accountability in the supply chain, as the cobalt is processed into semi-finished materials and passed along to other intermediaries.

A similar situation unfolds in Indonesia, where mining companies are legally required to pursue downstream processing in accordance with Law No. 3 of 2020 on Mineral and Coal Mining. This regulation mandates that mined minerals be processed domestically and not exported in raw form. Although the policy aims to enhance export value and product competitiveness, it poses specific challenges for cobalt as a commodity. Unlike the DRC, where cobalt is a primary product, in Indonesia, it is a byproduct of processing laterite nickel. As a result, Indonesian cobalt is typically of lower purity, between 0.1% and 0.2%, compared to 1% to 2% in the DRC, necessitating more intensive and costly refining processes such as high-pressure acid leaching (HPAL) to meet battery-grade standards.

Cobalt mining in Indonesia is dominated by local and foreign companies, most of which are backed by Chinese firms. This has raised concerns among Western tech companies about the traceability and reliability of Indonesian cobalt, especially regarding ESG compliance. These concerns are compounded by growing geopolitical tensions between the West and China and Western skepticism toward Chinese technology.

Labor practices also play a key role. Glencore has faced serious allegations of human rights violations, including child labor. Of the estimated 225,000 local miners in the DRC, around 40,000 are believed to be children, working over 12 hours a day for wages lower than their adult counterparts. These issues are exacerbated by weak oversight and the lack of safety standards. Child labor exploitation is predominantly found in artisanal mining operations practices that many tech companies regard as grave human rights violations. Conversely, Indonesia does not rely on artisanal mining and emphasizes formal operations that must comply with ESG regulations under national law. Mining projects are required to conduct Environmental Impact Assessments (AMDAL) to ensure that environmental and social aspects are considered from the outset.

The technological capabilities and infrastructure of foreign mining companies also influence the cobalt supply chains in both countries. Due to limited domestic capacity, both Indonesia and the DRC remain dependent on foreign technological expertise, serving primarily as labor providers while foreign entities maintain control over oversight and decision-making. Ironically, despite their mineral wealth, both nations remain labor suppliers rather than primary beneficiaries of their own resources. In the DRC, this dependency has led to deep entanglement with foreign companies, often resulting in conflicts of interest between local stakeholders and multinational firms. It has also fostered corruption, collusion, and nepotism in mining permit processes, exacerbated by weak institutional authority.

ESG compliance does not always align with the sustainability commitments promised by technology companies. ESG implementation in cobalt mining has not yet been robust enough to prompt tech firms to shift operations to Indonesia. Direct access to supply chains and reliable delivery guarantees have made these companies more inclined to stick with Glencore, which has a proven track record and the large-scale supply capacity they need. This is reinforced by long-term contract extensions with several companies agreeing to purchase specific volumes of cobalt directly from Glencore. Trust in Indonesia’s cobalt sector remains low, primarily due to Chinese dominance and doubts over the country’s industrial capacity to meet high-volume tech demand.

Even with ongoing ESG issues in the DRC, tech companies remain reluctant to move their supply chains to Indonesia. The DRC retains a competitive edge through lower production costs and simpler refining processes. Additionally, regulatory laxity and inadequate policy frameworks allow mining firms and their tech partners to sidestep ESG obligations in favor of higher output. This creates the risk of greenwashing—where companies present a false image of sustainability that doesn’t match on-the-ground realities.

Indonesia’s stringent regulations and bureaucratic hurdles are another deterrent. The downstream processing requirement limits tech companies’ ability to maintain accountability and control over their cobalt sources. Reputational risks and growing consumer pressure for ethical and transparent supply chains further complicate the situation. Without direct oversight, tech firms find it difficult to guarantee supply consistency, as the chain is vulnerable to socio-political and logistical disruptions. Nonetheless, Indonesia’s rising cobalt production signals immense future potential. Although the DRC still leads in cobalt quality, Indonesia offers a stronger regulatory framework to ensure ESG compliance while mitigating environmental and social harm. This makes Indonesia an appealing long-term partner for tech firms committed to sustainable innovation and clean technology. While ESG implementation is rarely perfect, it reflects genuine efforts by technology companies to uphold their sustainability commitments, particularly when supported by transparent reporting and auditing systems.

Collaborative engagement among stakeholders is essential to building an ESG-compliant cobalt supply chain. A coordinated network involving governments, mining firms, tech companies, labor communities, and consumers is needed. Such collaboration can foster inclusive public participation and develop a structured and transparent monitoring system to prevent ESG violations. A top-down approach from the government can establish a centralized communication framework supported by good governance to protect workers and ensure the sustainability of the cobalt mining industry.

Indonesia and the Democratic Republic of Congo represent two major cobalt producers in the Global South. Both are undergoing reforms to restructure domestic and foreign mining institutions and strengthen policy frameworks supporting ESG compliance. In an effort to maintain balance in the global cobalt market, the DRC plans to impose export quotas following a four-month export ban that helped stabilize global cobalt prices. It is also exploring a partnership with Indonesia, the world’s second-largest cobalt producer, to jointly regulate global supply and stabilize prices. The DRC is also considering implementing domestic processing requirements similar to Indonesia’s downstream mandate, though this initiative remains under review. The DRC’s outreach to Indonesia signals that the country is seen as a strategically positioned and competitive cobalt producer, given its head start in nickel downstreaming. This opens up opportunities for enhanced cooperation and the exchange of best practices in cobalt processing.

While DRC cobalt commands a higher market value, Indonesia holds a significant advantage in ESG compliance, a promising factor for foreign investors committed to technological innovation. There is a need to reassess domestic policies that currently deter foreign investment without compromising ESG standards. Emphasis should be placed on downstream processing that adds value to the final product. Moreover, involving formal workers and increasing control by local mining companies can minimize conflicts of interest and reduce corruption, collusion, and nepotism in the sector. Indonesia’s relatively strong ESG compliance can serve as a springboard for further improvement and as a signal that Indonesian cobalt can also be a competitive force in the global market.