Mining Other

Guinea-Africa’s “most Australian country” heads to the polls

First launched over 20 years ago to highlight Australia’s interests in African mining and energy, the Africa Down Under Conference has become the largest African-focused mining event outside the African continent. This year’s gathering in Perth once again brought together senior African and Australian officials and business leaders.

Among them was Guinea’s Minister for Planning and International Cooperation, Ismael Nabé, who described Guinea as “the most Australian country in Africa”. He pointed to parallels in mining and agriculture, noting both countries’ reliance on these sectors.

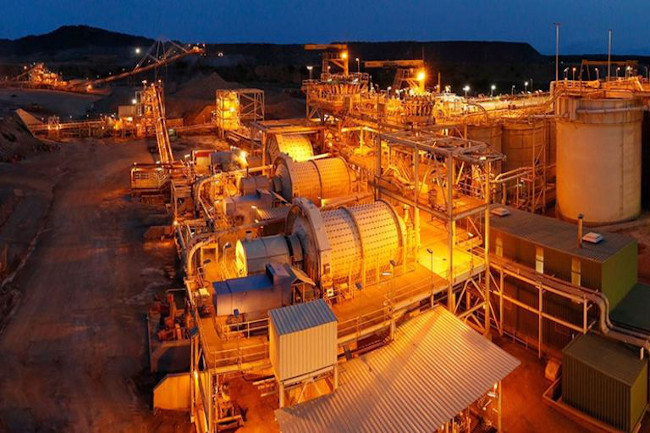

The comparison has merit. Guinea is home to Simandou, the world’s largest undeveloped high-grade iron ore deposit. Australian companies, notably Rio Tinto, have been engaged there for years. This month it was revealed that Rio Tinto and its Simandou iron ore partners will receive tax discounts of more than 50% from the current Guinean government on crucial parts of their $35 billion project. The government has pledged that the resulting revenues from the “Simandou 2040” project would finance increased social spending, some of which would fund scholarships for Guineans to study abroad, including in Australia.

The optimism in Perth contrasts with the political reality in the capital of Guinea, Conakry. The conference coincided with the fourth anniversary of Guinea’s 2021 coup, when Colonel (now General) Mamady Doumbouya ousted President Alpha Condé. It also came just weeks before a constitutional referendum scheduled for 21 September 2025.

The 2021 coup was initially welcomed by many Guineans, weary of Condé’s controversial third term. The junta pledged a return to constitutional order by the end of 2024. That timeline has slipped. The process is now described not as a political “transition” but as a broader “refoundation” of the state.

The draft constitution removes a key safeguard from the transitional charter that barred military officers from running for office. This omission has reinforced suspicions that the junta is seeking to entrench its power rather than effect a genuine democratic transition. At the same time, a nationwide campaign has elevated Doumbouya as the likely next president. In the absence of an official date for the presidential elections, many observers view the referendum less as a vehicle for constitutional reform than as a proxy vote on his leadership.

The conditions for the referendum are highly uneven. The pre-election environment shows serious shortcomings: an incomplete and contradictory legal framework, elections managed directly by the Ministry of Territorial Administration and Decentralisation (MTAD) through its General Directorate of Elections rather than an independent commission, the militarisation of public life, and the heavy use of state resources for the “Yes” campaign.

Growing suppression has frozen political activity, journalism and civic engagement. Although the 2021 coup was largely bloodless for civilians, civic and political space has progressively deteriorated. High-profile cases of forced disappearances, as well as torture and judicial harassment of opposition leaders, journalists and former officials, have further deepened the climate of fear and weakened dissent. Security forces, accused of abusing their authority, maintain a visible presence in public life.

Political parties have been weakened by a 2022 decision banning all public protests and confining them to their offices. A sweeping review carried out by MTAD led to political party suspensions and dissolutions, amid accusations of government interference aimed at destabilising the opposition.

Exiled political leaders — including former president Alpha Condé and opposition figure Cellou Dalein Diallo of the Union of Democratic Forces of Guinea — face imprisonment if they return, effectively excluding them from political participation.

Since 2023, the government has shut down several media outlets, reducing citizens’ access to balanced information at a critical moment. These closures have often been justified on compliance grounds, with authorities invoking regulatory violations or accusing outlets of engaging in “illegal activity”. Instead of creating space for neutral voter education, authorities campaigned for the Yes vote through rallies, cultural events and sports activities.

Although a campaign to enrol voters for the new electoral roll took place, the absence of an independent audit risks undermining trust in the register, given Guinea’s history of disputed voter lists. Concerns also remain that the uneven distribution of voter cards, which began on 6 September 2025, could be used to suppress voting in certain areas.

Guinea’s electoral law restricts observation to polling day, limiting scrutiny of the broader process. The risk of “fake observers” — aligned with the government — further threatens credibility. The Supreme Court is charged with resolving disputes but its independence is widely questioned.

Guinea’s international and regional obligations — under the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights, the African Charter on Democracy, Elections and Governance and the Protocol on Democracy and Good Governance of the Economic Community of West African States — require respect for political freedoms, independent institutions and credible elections.

The 2021 coup d’état and its prolongation under the concept of “refoundation” directly contradict the prohibition on unconstitutional changes of government. At the same time, enforced disappearances and torture raise serious concerns under the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court.

Instead of restoring constitutional order, the referendum risks consolidating authoritarian rule and deepening Guinea’s legitimacy crisis. As referendum day approaches, several risks stand out.

Informed choice undermined. Citizens may be denied access to balanced information, limiting their ability to make a genuine electoral choice.

Escalation of repression. Intimidation of opposition parties, journalists and civil society could intensify.

Legitimacy deficit. Excluding key opposition forces risks producing a constitution without sufficient authority to guide the post-transition phase.

Militarisation of politics. A heavy security presence risks normalising elections as military operations rather than civic processes.

Instrumentalised observation. Government-aligned or “fake” observer groups could be used to legitimise a flawed process.

Weak international accountability. With global attention focused elsewhere, external pressure on Guinea to uphold democratic standards is likely to remain limited.

Mining revenues will flow not only to Guinean state coffers but, indirectly, to Australia. However, for Australia, Guinea matters not only as a mining partner but also as a test of responsible international engagement. Past experiences, such as that of Panguna in Bougainville, show how poorly managed resource wealth can drive conflict and undermine governance.

As Guineans head to the polls, Australian stakeholders must act responsibly to avoid the risks of exacerbating local tensions, empowering authoritarian actors or fueling instability.