Mining Other

Chinese Nationals’ Role in Africa’s Illicit Weapons, Mining, and Money Flows

By: China global south project

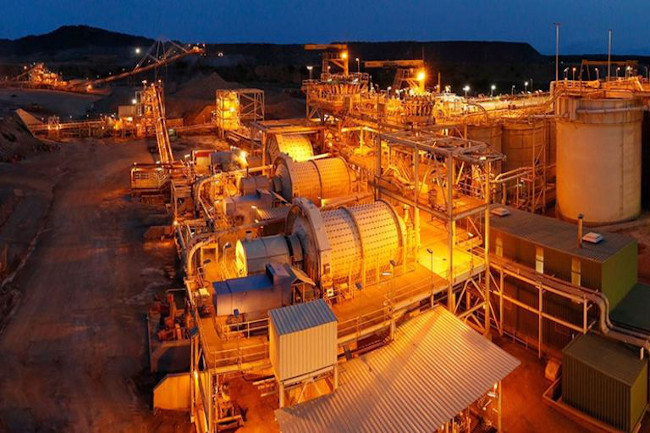

There is mounting evidence that Chinese organized crime syndicates are shifting their operations from Southeast Asia to Africa, contributing to a surge in illicit activities such as crypto mining, scam centers, illegal wildlife trafficking, and black market weapons sales. This trend poses a significant threat to African countries with already weak governance systems, making them particularly vulnerable to these transnational criminal networks. The discussion, led by researcher Adam Rousselle, explores how these various illegal trade networks are often interlinked, creating a complex web of illicit finance and goods.

A central theme of the analysis is the critical distinction between the actions of individual Chinese criminals and the Chinese state. Rousselle and the podcast hosts emphasize that there is no substantial evidence linking these illicit activities to a coordinated effort by the Chinese government. Instead, these are largely opportunistic actions by individuals and networks taking advantage of governance gaps and corruption in various African nations. Chinese embassies have often stated that if their citizens are breaking local laws, they should be arrested and prosecuted.

The conversation highlights several specific examples, including a court case in South Kivu, DRC, involving Chinese nationals in illicit gold smuggling, and the rounding up of Chinese criminals in Nigeria's cryptocurrency economy. Furthermore, the discussion addresses the concerning appearance of Chinese-made weapons in conflict zones like Sudan and Mali. Importantly, it is clarified that these weapons often arrive via third countries like the UAE through illegal diversions from legitimate stockpiles, rather than through direct supply from China.

A significant part of the problem lies in the local complicity and weak governance within African countries themselves. The dialogue points out that local politicians, military officials, and brokers often enable these illicit activities through corruption and political protection. This creates a scenario where even when arrests are made, individuals may be released due to local interference, frustrating efforts to enforce the law and leading to public misconceptions that Chinese embassies are applying diplomatic pressure for their release.

Despite the lack of state coordination, the scale of these activities presents a serious reputational risk for Beijing. The pervasive presence of Chinese nationals in illegal operations and the circulation of Chinese-made weapons in conflict zones create a perception problem that the Chinese government is compelled to address. While Chinese officials have issued warnings and, in some cases, cooperated in arrests, the challenge remains significant due to the decentralized and networked nature of these criminal enterprises.

The discussion cautions against oversimplified media narratives, particularly from Western outlets, that often conflate the actions of Chinese individuals with state intent. Such framing can distort the complex realities on the ground and ignore the role of local agency and responsibility. The analysis calls for a more nuanced understanding that places these illicit flows within the broader context of global shadow finance and local governance failures, rather than attributing them to a monolithic Chinese strategy.

In conclusion, tackling this issue requires a collaborative, transnational response that involves improved local law enforcement, international regulatory cooperation, and more assertive action from Beijing to curb the activities of its nationals abroad. While the Chinese government faces a dilemma in balancing its non-interference policy with the need to protect its reputation, addressing these illicit networks is crucial for fostering stability and sustainable development in Africa.